Every day when I go to work, I see a fresh horde of tourists valiantly trying to Do Tourism in the financial district. They don't really have much choice in the matter: this is, after all, the first neighbourhood listed in their New York City travel guides, and even a decade after 9/11, most of these books still make an effort to say something nice about the area. Unfortunately, as anyone who thinks seriously about the words "financial district" will quickly realize, this a deeply boring part of the city. Visitors come blinking into the light at the Wall Street Subway Stop, and then, encountering a dearth of things to marvel at, turn around and take pictures of the Wall Street Subway Stop. Alternatively, they photograph their friends cupping the testicles of the financial district bull, which have been polished shiny by the troupes of equally original and hilarious performance artists who have come before.

All of which observations may invite the question, why am I being such a pompous, patronizing douchebag about the tourists in New York? Is it because I am insecure about my own less-than-resident status in the city? Or is it simply apish mimicry of other arrogant, tourist-adverse New Yorkers?

Yes and yes! But there's third reason as well: I have, through no merit of my own, discovered the prima financial district attraction. I refer, of course, to ringing practice at the Trinity Church bell tower.

Trinity Church is located on the western end of Wall Street. You can see it framed dramatically between two skyscrapers if you approach from this side, and I personally think it would be quite a powerful closing to a movie to have the prodigal day trader, horrified by what he has become, running up the darkened canyon of the street in slow motion to seek redemption at its end. The movie would probably downplay the fact that Trinity Church itself is something of a tycoon among religious institutions: for an annual rent that is literally one peppercorn, it has become one of the largest landholders in New York City. It's also got that certain intangible, spiritual kind of wealth that comes from having the first United States Secretary of the Treasury - the great Alexander Hamilton - lying dead in the backyard. No other church in the world can make that claim.

And then there are Trinity's church bells - twelve of them, to be exact. This is apparently a very large number of bells to have in a single tower, and, as I would later learn (and as my fictional Wall Street day trader already knew) such abundance has its drawbacks. "Other bands of bell ringers sometimes don't even want to talk to us at the annual convention," a member of the Trinity band informed me gravely. "They've got six, eight bells, and here are we a round dozen! You can see why they're jealous." He paused a moment, pondering the mysteries of human envy. "We're also a much hipper band than most of the others."

"Hip" is not the word that sprang immediately to mind when I climbed up three flights of stairs and a ladder into the bell tower and saw twelve sundry people standing in a circle, rhythmically pulling on ropes while staring fixedly forward. Apparently the rest of the students at my firm came to the same conclusion, without even needing to observe the scene for themselves. Of the eighty-odd people who received an invitation to go to Trinity Church - this from a lawyer who has long nurtured an unfulfilled love of bell ringing - I was one of only three who accepted. When I had asked my friends if they too were going, they looked at me pityingly, as though I had fallen for a very obvious prank.

But this was no prank. I should have made clear at the beginning, as it was made clear to me, that joking and church bells do not mix. "DO NOT LARK ABOUT IN THE RINGING CHAMBER" was the first rule set down in the instruction manual I was told to read when I arrived. The highly sensible ban on interior larking about also extended, as far as I was concerned, to actually ringing the bells. Just as pilots have to go to ground school before they're allowed to get in the cockpit, so did I, it turned out, have many long hours of watching people clang metal objects together before I could attempt this sacred art myself.

As a consolation, one of the ringers, a great praying mantis of a man in “Caltech Dad" T-shirt, offered to let me hold the end of the rope while he rung the bell. This arrangement effectively neutralized the deadly risk - literally deadly, the ringers frequently told me with relish - that I might ring the bell improperly, and freed my mind to absorb Caltech Dad's gentle stream of constructive criticism concerning my rope holding. In between the clanging and the “eyes forward!” (occasionally glancing somewhere besides straight ahead is a classic beginner rope-holder’s mistake), I also picked up some edifying lessons on practice of bell-ringing as a whole.

For example: did you know that there are several completely different ways to arrange a group of bells within a tower for ringing? Surely you did not. Probably the most familiar setup is the carillon, which is a group of bells organized such that they can be made to produce beautiful melodies by a single musician sitting as a keyboard. Absurd, no? The kind of ringing we were doing, on the other hand, is called “change ringing.” It requires one ringer per bell, along with much roaring and haranguing by the band leader to keep the many disparate elements in line. And don’t bother trying to produce such a frivolity as a “tune” from a set of change-ringing bells: can’t be done! Change ringing is the speed walking of the music world – a pursuit seemingly defined by its rigid restrictions and limitations – which probably explains both its circumscribed public appeal and the fanatical devotion of its few true disciples.

Instead of melodies, change ringers play things called “changes,” which are basically scales with various notes rearranged according to the dictates of mathematical formulae. The changes have names that sound like the labels for cruel British public school hazing rituals, including Pudsey Surprise, Old Oxford Delight, and the truly ominous-sounding Reverse St. Nicholas. They were introduced to me through the bellowing calls of the band leader, a surprisingly young Brit who looked like a bouncer and seemed oddly out of place yanking a rope in a two hundred year-old bell tower. With every jauntily-named new order, the algorithm guiding the order of bells would shift slightly, sending a new series of tuneless sound patterns echoing through the air.

So there we were: on a hot night in the heart of the financial district, where tourists scratch their heads and hard young men in Anderson & Sheppard suits pass each other without smiling, using math not to price derivatives, but to create beautiful (?) music! What kind of impression must we be making?

As it turned out, none at all. The windows in the tower are shut. The bells ring for hours, several nights a week. But nobody on Wall Street can hear them.

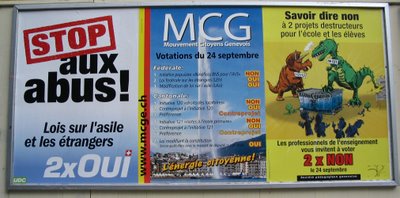

One of many memorials commemorating Switzerland’s valiant participation in World Wars Eins & Zwei.

One of many memorials commemorating Switzerland’s valiant participation in World Wars Eins & Zwei. Grown men bicker like children at an impromptu public chess game in Geneva. Even on rainy days, these Titans’ battles draw sizeable crowds.

Grown men bicker like children at an impromptu public chess game in Geneva. Even on rainy days, these Titans’ battles draw sizeable crowds.

Deborah and I put on tricks to confound the local villagers in Glarus, site of Europe's last execution for witchcraft.

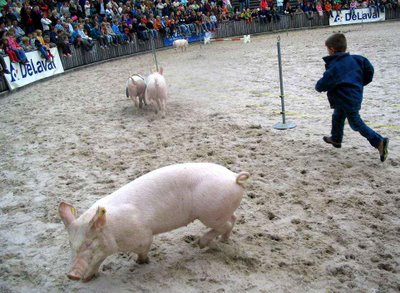

Deborah and I put on tricks to confound the local villagers in Glarus, site of Europe's last execution for witchcraft. Fleet-footed swine and a confused child strut their stuff at the races at Olma Fair, St. Gallen. In Switzerland, pigs are raced for entertainment and high-stakes gambling, while horses are carved up into sausages for human consumption. Furthermore, cows are entered into national beauty contests that everyone seems to take very seriously.

Fleet-footed swine and a confused child strut their stuff at the races at Olma Fair, St. Gallen. In Switzerland, pigs are raced for entertainment and high-stakes gambling, while horses are carved up into sausages for human consumption. Furthermore, cows are entered into national beauty contests that everyone seems to take very seriously.  An age-old Swiss tradition in Rütli: waving red flags to scare away prospective immigrants.

An age-old Swiss tradition in Rütli: waving red flags to scare away prospective immigrants.

Sometimes an eight-foot-long phallic wind instrument is just an eight-foot-long phallic wind instrument: alphorn players celebrate Swiss nationhood with a venerated stereotype.

Sometimes an eight-foot-long phallic wind instrument is just an eight-foot-long phallic wind instrument: alphorn players celebrate Swiss nationhood with a venerated stereotype. Combining Italy's sun and scenery with Switzerland's capacity for running a country that isn't a flagrant embarassment to the European continent, Il Ticino is probably the best place in the world.

Combining Italy's sun and scenery with Switzerland's capacity for running a country that isn't a flagrant embarassment to the European continent, Il Ticino is probably the best place in the world.